A Courant Complicity, An Old Wrong

The Hartford Courant

"To be sold ...

When Aetna Inc. apologized in March for insuring slaves, The Courant ran the story on the front page.

"a likely, healthy, good-natured NEGRO BOY ...

In another Page 1 story the next day, the paper explored the complicity of other businesses in propping up the nation's shameful institution.

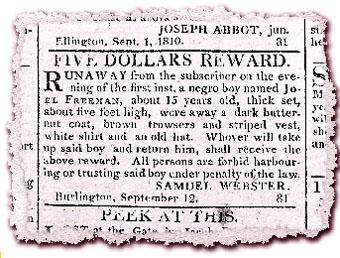

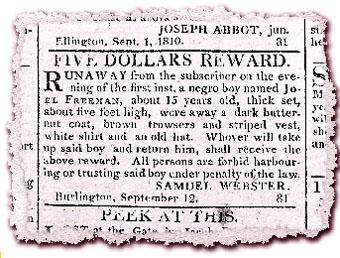

"about 15 years old ...

But the stories about Connecticut's slave profiteers had a glaring omission: The Courant itself.

Inquire of T. Green."

From its founding in 1764 well into the 19th century, The Courant ran many ads for the sale and capture of human beings, including the example above from May 1765. In effect, Courant publishers, including founder Thomas Green, acted as slave brokers.

It was accepted practice. Slavery was so woven into the nation's economy and social fabric that such ads were probably less controversial than gun or tobacco marketing would be today.

"I don't know of any newspaper which took a stand against taking advertisements for slaves unless they were (abolitionist) papers that were committed to ending slavery," said Ira Berlin, a professor of African American history at the University of Maryland and author of the acclaimed 1999 book "Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America."

Scholars have long known about the prevalence of such ads, but Hartford students researching the city's African-American heritage were astounded.

"I will never, ever forget the looks of dismay on their faces as they were scrolling through all the microfilm and finding these ads and for-sale notices," said former Hartford teacher Billie Anthony, who helped middle school students with the research several years ago.

One of those young black students, Andriena Baldwin, said she remembered in particular an ad listing a young boy along with pigs, butter and other commodities for trade.

"We just stood there for, like, five minutes," said Baldwin, who will be a senior this fall at Westminster School in Simsbury. "We were just shocked that they would put a person in the same category as food."

Detailed Descriptions

Blacks had been enslaved in the state since 1640. They were used primarily as domestic servants and farmhands. Many of the state's prominent families - Wadsworths, Seymours and Wyllyses - owned slaves.

In 1774, Connecticut had the most black residents among the New England colonies - about 6,500 people, representing about 3 percent of the population. The black slaves in this region, for the most part, did not face the dawn-to-dusk, stooping labor and intense abuse suffered by their counterparts in the mid-Atlantic and Southern states.

"The treatment of slaves was different at the North from the South; at the North they were admitted to be a species of the human family," James Mars, a former slave who lived in the northwest corner of the state and the Hartford area, wrote in his autobiography.

Still, African Americans in Colonial Connecticut could not vote, had to carry passes outside the towns where they lived and could be whipped for minor transgressions, including any threat to a white person. They could be sold away from their families at any time.

In his 1798 autobiography, former Connecticut slave Venture Smith told of being separated from his wife and young daughter for 18 months. He also wrote about a run-in with his owner's wife and the beating he suffered when the master returned.

"I received a most violent stroke on the crown of my head with a club two feet long and as large around as a chair post,'" Smith wrote. "This blow very badly wounded my head, and the scar of it remains to this day."

Some of this abuse surfaced in the newspaper ads for runaways, generally the only forum in which slave owners had to be completely honest about the condition of their property. The ads, which described scars, brandings and amputations, bolstered abolitionists' arguments that slavery was evil.

The detailed descriptions, right down to the pewter buttons on one runaway's coat, also proved a treasure for historians researching slavery.

"Those ads have become extremely useful to scholars because they are one of the few places that describe slaves physically, their appearance, what type of clothes they wore, whether they were literate, what type of talents they had," said Richard Newman, research officer at the W.E.B. DuBois Institute for Afro-American Research at Harvard University. "While slaves are treated impersonally as a group, when one runs away, then we get a personal description."

Slave hunters pored over the ads, looking for runaways with prices on their heads.

"It was a professional job - just like bounty hunters," Newman said. "It's a major enterprise."

However, Karl Valois, a history professor at the University of Connecticut, said slave hunters were rare in the state. "There wouldn't have been enough fugitive slaves in Connecticut or the North, for that matter, to make it worthwhile," Valois said.

Almost all of the ads for runaways did offer cash rewards. Many owners also offered to cover expenses of those who returned slaves. The Courant was circulated throughout the state, so citizens looking for supplementary income would have taken notice.

Complicity

The question, then, is: How successful were the ads and how much did The Courant profit from slavery?

The full answer will never be known, but historians say the fact that slave owners continued paying for the newspaper space - about 25 cents in 1768 for 10 lines running for three weeks - shows they had some effect.

"At least in the Colonial period, they did seem to work," Berlin said. "The runaways followed the same transportation routes that newspapers did. It would raise an alarm along that path."

"The ads had to be effective," Newman said. "There's no photography so there has to be physical descriptions."

Deadria Farmer-Paellmann, a 34-year-old lawyer and activist whose research into Aetna Inc.'s 19th century practice of insuring the lives of slaves prompted the company to issue a public apology in March, said she would not rule out asking The Courant and other newspapers that ran slave ads to apologize. But Farmer-Paellmann said such ads have not been a priority in her research. Farmer-Paellman said she hopes to establish a trust to hold restitution payments dedicated to improving the living standards and education of black Americans.

"I have not actually considered newspapers in that context," she said. "What I thought about at one time was whether any of the papers actually had slaves working for them. That is probably what I'd be more interested in.

"But I would say that if you would like to make an apology, that's great," she said.

"Unfortunately, the practice of advertising for slaves was commonplace in newspapers prior to abolition," said Ken DeLisa, a spokesman for The Courant. "We are not proud of that part of our history and apologize for any involvement by our predecessors at The Courant in the terrible practice of buying and selling human beings that took place in previous centuries.

"In fact, The Courant has editorially called on the president and on Congress to acknowledge `a dreadful part of their nation's otherwise grand legacy' and issue an apology on behalf of our government ("Should There Be An Apology?" June 22, 1997). We can do no less as an institution," DeLisa said.

That's a long way from the views of editors and owners early in The Courant's history.

The paper was never pro-slavery; editors took strong stands against its expansion into new territories. But the views of early editors were undeniably racist. Thomas Day, who bought the paper in 1855, often gave readers large doses of his - hence the paper's - racial theory.

"We believe the Caucasian variety of the human species superior to the Negro variety; and we would breed the best stock," Day wrote in one editorial.

The Courant did not openly embrace emancipation until the Civil War was well under way.

Nevertheless, many Northerners thought slavery did not mesh with the Revolutionary cry for freedom, and slave ads throughout the region began to fade soon after local patriots took up arms against their British oppressors.

"From about the Revolution on, the economic importance of those ads just continually declined in Northern newspapers. They become rare in Northern newspapers around 1810," said John Nerone, a professor of media studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

But they did appear occasionally in The Courant, until at least 1823. In August of that year, Elijah Billings of Somers placed an ad announcing that "a mulatto boy" named William Lewis had run off. Notably, Billings offered a reward of only one penny for William's return. Slavery was outlawed in the state in 1848.

Billie Anthony, the former Hartford teacher who now teaches in Bloomfield, says she and her students were, in the end, grateful that history had been preserved in The Courant's slave ads.

"The nation's oldest continuously published newspaper is a treasure for historians," she said. "The complicity of the Connecticut Courant in the slave trade is evident, and we may not always like what we find, but the truth is valuable."

Back to Historical Views

^^ Back to top

|